Bought to you by Gavin A.K.A. "Scaramouche"

~ Privacy Policy ~ Copyright Statement ~ Site Map ~ Site Updates ~ Contact Me ~

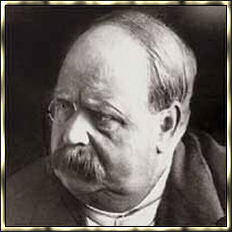

Sir George Reid KCMG, GCMG, GCB, CH, PC, KC

4th Prime Minister.

Sydney High School.

Commenced his medical course at age 15

University of Sydney 1895-1902

Master of Surgery (Sydney)

Bachelor of Medicine (Sydney)

Businessman

Grazier

Jean Thomas 20 July 1959.

Douglas (1916).

PC (Privy Counsellor) 1929

KCMG (Knight Commander of The Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael & St. George) 1909

GCMG (Knight Grand Cross of The Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael & St. George) 1911

GCB (Knight Grand Cross of The Most Honourable Order of the Bath) 1916

CH (Companion of Honour) 1942

Foundation Fellow Royal Australian College of Surgeons.

Honorary Fellow Royal College of Surgeons of England (1942)

First Chancellor University of New England (1955-61)

Honorary Doctor of Science (Sydney, New England, New South Wales).

Served as a Surgeon in the Australian General Hospital, Abassia, Egypt.

Also served at No.3 Australian Casualty Clearing Station, France.

Discharged, July 1917.

PLEASE NOTE: Both these links will open in a popup window

George Houstoun Reid was a Scot, born on 25 February 1845 at Johnstone, Renfrewshire. He was the fifth of seven children born to Marian Reid and John Reid, a Presbyterian minister. In May 1852, the Reads' were among the hundreds of people who arrived in Melbourne during the gold rushes. Reid went to school at the Melbourne Academy (later Scotch College). In 1858 his parents moved with their three youngest children to Sydney, and 13-year-old George Reid started work as a clerk in a city merchant's 'counting house'.

At the age of 15 he joined the School of Arts Debating Society, where democratic reforms such as manhood suffrage were passionately argued. Reid was among the most eloquent and ardent members of the Society throughout his 20s and recruited, among others, Edmund Barton and Richard O'Connor. Places like the society's Pitt Street rooms enabled these young men to make contacts essential for their advancement. In the case of Barton and O'Connor, the society added to the opportunities offered at school and university. Reid's drive and intelligence attracted essential connections, and he developed an easygoing and cheerfully impervious amiability. This characteristic was to make him a key parliamentary player - fast with a retort and rarely harbouring resentments. It brought him the criticism of deeper thinkers and more polished stylists, and also the warm response of voters.

At the age of 19, he went from the counting house to the rapidly growing public service. He first gained a post in the New South Wales Treasury and progressed to chief branch clerk. By 1878, aged 33, George Reid headed the Attorney-General's department. By then, he had published three notable works on political questions. His 1873 pamphlet The Diplomacy of Victoria on the Postal Question argued the New South Wales case for extending the route of mail steamers to Sydney, as the terminus was Melbourne. Two years later Five Free Trade Essays compared the effects of protective tariffs in Britain, the United States and Victoria. It was a controversial book that earned Reid honorary membership of London's Cobden Club. The third work, his book An Essay on NSW, Mother Colony of the Australia's, was part of the colony's contribution to the grand exhibition in the United States to celebrate the 1876 centenary of the signing of the US Declaration of Independence.

But throughout the 1870s George Reid had his eyes, if not always his attention, on qualifying as a barrister. For him, the law was the only real path to politics - the means of earning a living since parliamentarians were unpaid. Within a year of his admission to the Bar on 19 September 1879, he had resigned from the public service so as to be eligible to nominate as a candidate for East Sydney. In November 1880, Reid arrived, taking a seat in the Legislative Assembly in Macquarie Street for the first time. He held this seat for the next twenty years. A brief gap in 1884-85 marked the only electoral loss in a career that spanned forty years and three legislatures. The only electoral loss of Reid's career was in 1884, when he was unseated in a by-election. It was the only time his redoubtable popularity did not rise above all else for those whose interests he represented.

A strong and, unlike Barton, unshakeable supporter of free trade, Reid's personality, politics and principles made him an electoral winner in a strongly free trade colony. He was an influential liberal who energetically promoted public education and public libraries. He also worked for reform of the civil service and appointment on merit rather than patronage. Despite the ensuing loss of a ready source of revenue for the government, Reid was committed to reform of the 'selection before survey' land laws which had promoted fraud and malpractice.

Unattached to any of the multiple shifting factions that dominated colonial parliaments, Reid declined to join Henry Parkes' ministry. He continued his support of the Parkes government, but retained his independence to argue against specific legislation and policies inside and outside the parliament. Reid's liberal principles meant he was vigorously opposed to the Chinese Immigration Restriction Act 1889, supported by the labour movement as well as by many of his free trade colleagues.

In 1889 Reid was a founder of the Free Trade and Liberal Association of New South Wales. Together with the opposing Protectionist Union and the Labour Electoral League, it became one of the three political parties that dominated the last colonial decade and the first 10 years of Federation. Though a supporter of Federation in principle, Reid was suspicious of the rapid embrace of Federation by Henry Parkes and Edmund Barton. His judgement was reinforced when Barton abandoned free trade, seeing it as a barrier to achieving agreement with the other five colonies, and became a Protectionist. After the Australasian Federal Convention in March-April 1891, Reid voiced strong opposition to the constitution drafted at the convention. He argued that it undermined the colony's free trade policies, and that increased financial power for the proposed lower House and a less powerful Senate were vital. Six months after the convention, in November 1891, the 46-year-old Reid was elected leader of the Free Trade Party, and became Leader of the Opposition in the New South Wales parliament.

At the July 1894 election, Reid roundly defeated Barton, who had been out of parliament for three years. In contrast, Reid became Premier and led the government of New South Wales for the next five years. Among his ministers was former Labor Party member Joseph Cook, now a Free Trader. In May 1897 George Reid went on a four-month visit to England for Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee and the Imperial Conference. As Premier, Reid had become a key figure in the revival of Federation. At the Bathurst "people's convention" in 1896 he committed himself to bring Queensland into the union. On his London visit he met with Joseph Chamberlain, Britain's Colonial Secretary, to report on the progress of Federation and, with the other five premiers, was made a Privy Counsellor.

Reid returned soon after the opening of the 1897-98 Federation convention in Adelaide to take up his role as delegate. He had polled second to Edmund Barton among the New South Wales delegates. For Barton, Federation came first; for Reid, New South Wales was the primary concern - Federation of the colonies must be in the colony's interests.

The Federation impasse was resolved at a "secret" Premiers' conference at Melbourne's Windsor Hotel, opposite the Spring Street Parliament House, held over six days from 29 January 1899. The compromise clause proposed by Tasmanian Premier Edward Braddon meant the Commonwealth must return to the States a proportion of all tariff and duties. To Reid's satisfaction, the ongoing battle between Victoria and New South Wales over the sitting of the national capital was also settled. Under the compromise, the site would be in New South Wales, but not less than 100 miles from Sydney.

With women still prevented from voting, New South Wales voters approved the amended Constitution Bill on 20 June 1899. With a reduced majority after the July 1898 election, Reid's government depended on an alliance with Labor leader William Holman. As the Bulletin observed, he then saw Labor as 'a hand worth holding'. Reid was just as opposed to Labor's caucus solidarity principle as his minister, Labor defector Joseph Cook, so this was not a secure arrangement. Moreover, though Reid had again trounced Barton in East Sydney in the July election, Barton secured the Assembly seat of Hastings-Macleay in a subsequent by-election and was now Leader of the Protectionist Opposition.

Losing the premiership deprived Reid of a hope of becoming Australia's first Prime Minister. Deakin thought Reid capable of the revenge of devising "the Hopetoun blunder", when the Governor-General designate named William Lyne, not Barton, as Prime Minister in December 1900. In the absence of any evidence of Reid's involvement, this remains supposition, particularly as there is little evidence of Reid having a thirst for revenge throughout forty years of public life. On the other hand, it is fact that Barton excluded Reid from his first ministry. Pointing out that Reid had a far stronger claim than half the men included, historian LF Crisp referred to this as 'the most ungrateful excommunication'.

Early in 1900, while Barton and Deakin were leaving for London to ensure the passage of the Constitution Bill through the British parliament, Reid launched his federal election campaign. An intercolonial free trade conference in February began an 'energetic journeying' around Australia to promote Free Trade policies and prepare the way for Free Trade candidates.

Even without the advantage of a role in government from 1 January 1901, in the March election Reid worked his platform magic and was returned for the new federal electorate of East Sydney. Among the Sydney-siders elected to the first parliament were five of Australia's first seven prime ministers. All had been founders of the three parties in New South Wales: Edmund Barton (Protectionist); George Reid (Free Trade); and JC Watson, Joseph Cook and WM Hughes (Labor).

A key issue for the first parliament was establishing the import tariffs, the main source of revenue for the Commonwealth. For the Free Trade Party this posed a dilemma. Delay of the inevitable was their only course of action.

When the Treasurer tabled the tariff proposals on 8 October 1901, Reid made history by moving the parliament's first censure motion. This strategy set in train eight months of 'frittering struggle over details and a shameless repetition of stock fiscal arguments', as Deakin described the 'nightmare' of the prolonged debate in June 1902. When the first parliamentary session ended on 10 October, the most contentious of the four tariff measures had finally become the Customs Tariff Act 1902. This was achieved to the exhaustion of all, particularly Deakin, the acting Prime Minister during Barton's six months in London that year.

The new Governor-General, Lord Tennyson, opened the second session of the nation's first parliament on 26 May 1903. Under attack from Reid, Leader of the Opposition, and JC Watson, Leader of the Labor Party, the Barton government was immediately embroiled in debate over the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill and the Papua (British New Guinea) Bill. The latter was necessary for the acceptance of Britain's New Guinea as a Commonwealth territory, and the establishment of an Australian administration there. When Labor attempted to amend the Papua Bill so that the proposed Papua Legislative Council would be elected by the white population, Reid argued for the 'just rights of the blacks'.

A shrewd strategist as well as a persuasive debater, Reid made another historic gesture when he resigned his seat on 18 August 1903 to protest the Protectionist government's rejection of the Electoral Commission proposal for an additional Sydney seat. This was part of the redrawing of electorate boundaries for the second federal election. Reid was back in the House two weeks later, an East Sydney by-election having reinforced his position with his party and his constituents. The East Sydney voters were far from objecting to this additional democratic exercise, returning Reid again only three months later, at the federal election on 16 December 1903. His performance throughout the first parliament - like his policy statement "The fiscal problem: my fight for reform" for the federal election - reveals Reid as above all a liberal democrat and a 'parliament man' rather than a party disciple.

While the Free Trade Party held their position at the 1903 election, the Protectionists, led by Deakin (after Barton's elevation to the High Court in September) suffered losses picked up by Labor. The result was the short-lived Deakin government, defeated six weeks after the opening of the second parliament on 2 March 1904. Reid saw what Deakin called the 'three elevens' parliament (each of the three parties holding an almost equal proportion of the seats) as an opportunity for a liberal alliance. Despite the fiscal differences, Reid anticipated the shaping of national parties on liberal and labour lines. Deakin might have shared this prediction, but like Barton, he was rigidly opposed to Reid.

When a vote on the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill demonstrated that Deakin did not have the necessary majority in the House of Representatives, he was required to advise the Governor-General on whether an alternative government could be formed. Once more Reid awaited the Governor-General's call in vain. Deakin recommended that Lord Northcote ask JC Watson to form a government. The result was the installation of Australia's first Labor government on 27 April 1904. Though Deakin and Watson had a mutual respect and liking, the alliance was both unlikely and unstable. The new Labor government shared Deakin's recognition of Reid's potency as a parliamentarian and of his ability, given the opportunity, to put in place a program that was not only effectively free trade, but effectively anti-socialist.

His first move was to appoint Allan McLean, a Protectionist, as Treasurer. His administration was often referred to as the Reid-McLean government. But it was a flimsy alliance because Reid had no firm policy apart from waving the anti-socialist banner and securing the passage of legislation already before the House. During his first month of government, his party narrowly survived a no-confidence motion. Its only significant achievement was to allow the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill to 'drift' onto the statute books with a few minor amendments. Nine acts of parliament were passed during the period in office of G S Reid. Most important of these was the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904, establishing a court for settling industrial disputes. It was one of the most significant pieces of legislation in Australian federal history, effecting economic and social policy as well as industrial relations.

Deakin was sharpening a knife for Reid and, in July 1905, he used Labor support to cut him out of power. From that moment on, Reid lost much of his interest in federal politics, apart from supporting the closer alliance of Free Trade and Protectionists. He left most of the work of Leader of the Opposition to his lieutenant, Joseph Cook, while he concentrated on his legal practice. He retired from Parliament in 1908 and in 1910 accepted appointment as Australia's first High Commissioner in London.

Reid filled this office and soon gained entry into London society. He became particularly popular as an after-dinner speaker. In 1916 Andrew Fisher replaced him as High Commissioner but, by that time, Reid was so well established in Britain that the Liberal Party offered him a 'safe' seat in the House of Commons. He held the seat until his death in 1918, the only Australian ever to have sat in the Colonial, Commonwealth and Westminster Parliaments.

- He was the first High Commissioner to the UK.

- He was a Federation father.

- He was the only Free Trade Prime Minister.

- The first federal Opposition leader from 1901 to 1904

- Sir George Houstoun Reid, the only Australian to have sat in the colonial (New South Wales) parliament, the Commonwealth parliament and British parliaments.

- His was the first Australian prime ministerial funeral, in 1918.

The reference material used to compile this page is listed below:

The design, layout and contents of this page are Copyright by Scaramouche© 2000 - 2005

All Rights Reserved.