Bought to you by Gavin A.K.A. "Scaramouche"

~ Privacy Policy ~ Copyright Statement ~ Site Map ~ Site Updates ~ Contact Me ~

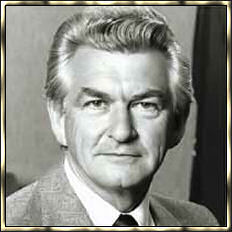

Robert James Hawke AC

28th Prime Minister.

University of Western Australia (1947-53).

Won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University (1953-56).

Bachelor of Laws (Western Australia).

Bachelor of Letters (Oxon).

Rhodes Scholar (Western Australia).

Blanche d'Alpuget, 1995.

PLEASE NOTE: Both these links will open in a popup window

Robert James Lee (Bob) Hawke was born on 9 December 1929 in Bordertown, South Australia. He was the younger of the two sons of Congregational minister Clem Hawke and Ellie (Lee) Hawke, a former teacher. In 1939, after Bob Hawke's 18-year-old brother Neil died, the family moved to Perth, Western Australia and settled in the suburb of West Leederville. Hawke attended Perth Modern School, then the University of Western Australia. Hawke was president of the University's Student Representative Council and graduated with a Law degree and an Arts degree in 1953. That year Albert Hawke, Bob Hawke's uncle, became Western Australia's Labor Premier. Bob Hawke went to Oxford University in 1953, as Western Australia's Rhodes scholar. Abandoning his planned degree, he submitted a thesis on the history of wage-fixing in Australia and he graduated with a Bachelor of Letters in 1955 and returned to Australia in 1956.

On 3 March 1956, he and Hazel Masterson married in Perth. They had first met eight years earlier. Hawke then enrolled in a doctoral program at the Australian National University and the couple moved to Canberra. Two years later, with the degree unfinished, Hawke took a job with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU).

Bob Hawke was the ACTU's first paid researcher and advocate before the Arbitration Commission. He soon proved his value. He played a key role in the 1959 basic wage decision and then succeeded in a metal workers' case before the commission. In 1962 Hawke was a delegate to a conference for nominees from Commonwealth countries, sponsored by the Duke of Edinburgh and held in Canada.

In 1963 Hawke's first attempt to enter federal parliament failed after he contested the seat of Corio (Victoria) against Liberal minister, Hubert Opperman. In July 1964 the Hawke's moved to a larger house in Royal Avenue, still in the bayside suburb of Sandringham, with their three young children. Their fourth child, a son, had survived only a few days after his birth a year before. In 1965 the family spent three months in Port Moresby, where Hawke was arguing a wage case for Papua New Guinea's public servants.

When Albert Monk retired as president of the ACTU in 1969, Hawke was elected his successor. During his ten years with the ACTU, Hawke transformed wage fixing in Australia and was acknowledged as the system's best advocate. He had developed good relations not only with unionists but also with his opponents, the employers and government representatives. His powers of persuasion were widely recognised, as was his conviviality - measured by copious beers over negotiations in hotel bars. He made strong friendships with Labor Party and trades union colleagues.

In 1971 Hawke travelled to Israel as the first recipient of an award in memory of Senator Sam Cohen. He then travelled to Geneva for a meeting of the International Labour Organisation governing body, of which he had become a member the previous year. From there he arranged to go to Moscow for meetings about the plight of the 'refuseniks', Jewish people unable to get permission to leave the Soviet Union. On his return to Melbourne, Hawke delivered the inaugural Cohen lecture. That same year the ACTU was also heavily involved in anti-apartheid demonstrations against the tour of the South African Springboks rugby union team.

Also in 1971 Hawke was elected to the federal executive of the Australian Labor Party and was made Father of the Year. In 1972, the Hawke's were both involved in Labor's campaign for the federal election. They were prominent at the triumphal celebrations when Gough Whitlam led the party to victory - the first Labor government since Ben Chifley was defeated at the 1949 election. Bob Hawke worked increasingly to resolve rather than instigate industrial disputes. He was active in international labour issues, and in Australia became the most prominent figure in the union movement, with a national reputation as an effective negotiator.

In 1973 Hawke was elected federal president of the Australian Labor Party for a five-year term. Now president of both the ACTU and the Labor Party, he represented the labour movement and the Labor Party on governing and advisory bodies, such as the Reserve Bank Board, the Australian Population and Immigration Council, and the Monash University Council.

In July 1973 the Hawke's travelled to Singapore, Tehran and Israel for meetings of unionists, and to Geneva for an International Labour Organisation meeting. In 1974 Hawke went to a labour conference in Belgrade, where Hazel Hawke and their children joined him to travel to Greece for a holiday. Holidays were rare, and this one was interrupted by phone calls and negotiations as usual on both party and ACTU business. At the Bass by-election in 1975, the loss of Lance Barnard's seat weakened the Whitlam government.

When Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed the Whitlam government on 11 November 1975, Hawke immediately left his Melbourne office for Canberra, and was prominent in both the protest demonstrations and the Labor campaign for the December election. Reflecting his preference for resolving rather than promoting industrial disputes, he held firm against calls for industrial action to protest Whitlam's dismissal. During these years Hawke was fighting a battle against alcoholism. He nonetheless managed a punishing workload. The worst effects of this problem were concentrated within his family life. When they emerged in his work life, they were concealed by close friends and colleagues.

Recognition of his work and achievements grew, both in Australia and overseas. In 1976 Hawke returned to Israel, as a guest of the Israeli government, for the dedication of a forest to him. He was invited to China in 1978 as a leader of the trade union movement and, in January 1979, he was made a Companion of the Order of Australia. In May that year he travelled to Moscow and Geneva, where he led unsuccessful negotiations on behalf of Soviet Jewish families attempting to emigrate. Invited to deliver Australia's ABC radio Boyer Lectures during 1979, Hawke chose as his topic 'The resolution of conflict'.

After a physical collapse in 1979, Hawke began a sustained attempt to conquer his alcohol addiction. In 1980 his popularity in Australia became evident in an opinion poll on preferred Prime Ministers. Though not even in parliament, he far outstripped both Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and Leader of the Opposition Bill Hayden. On 23 September 1980, Hawke announced his intention to make a second attempt to enter federal parliament, and on 14 October was pre-selected for the seat of Wills. He resigned from the ACTU to begin campaigning for the federal election. When Hawke won the seat of Wills in October 1980, leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party Bill Hayden appointed him Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations, Employment and Youth Affairs. Hawke made his first speech in the House of Representatives on 26 November 1980. At the age of 50, he might have been a new parliamentarian, but he was a seasoned, confident and persuasive politician.

In May 1982, the Hawke's travelled to Singapore, London and then Helsinki where Hawke attended an international socialist conference. At the Labor Party's federal conference in Canberra's Lakeside Hotel in July 1982, Hawke initiated a challenge to Bill Hayden's leadership. Hawke lost the Caucus ballot that followed, but the vote was close. The recognition within the party that Hawke's leadership ability outstripped all others, including Hayden, made a successful challenge just a matter of time. Hawke did not have support from the left wing party faction, but Hayden's stance against the left's wish to repudiate uranium mining policy made Hawke a lesser evil.

Senior Labor figures assembled in Brisbane on 1 February 1983 for the funeral of former Prime Minister Frank Forde, with former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam among the pallbearers. After the solemnities, Hayden held a long and emotional meeting with John Button, one of his closest colleagues, and finally agreed to step down. Two days later the Labor Party shadow Cabinet met in Brisbane and Hayden resigned. In Canberra a few hours later Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser met with the Governor-General to request a double dissolution of the parliament. Fraser had hoped to forestall the change of leadership before the election.

Hawke was elected Labor Party leader on 8 February 1983, and the federal election was called for 5 March 1983. Hawke was Leader of the Opposition for less than a month, and his most urgent task was the brief election campaign. The Labor Party campaign launch was held at the Opera House, Sydney on 16 February, under the slogan 'Bringing Australia together'. In the press statement announcing his resignation, Bill Hayden had said that in the current electoral climate, 'a drover's dog could lead the Labor Party to victory'. After a four-week campaign, Bob Hawke led the Labor Party to their greatest election win in 40 years. His parliamentary apprenticeship had lasted just two years.

Hawke brought the ALP back into government at the general election on 5 March 1983, by gaining a 15-seat majority over the Liberal-National coalition in the House of Representatives. He also held 30 Senate seats, compared to the 28 of the coalition, 5 of the Democrats and 1 Independent.

Concerned with the divisiveness of recent events, Hawke's first major step as Prime Minister was to conduct an 'Economic Summit' meeting in Canberra from 11 to 14 April 1983. The summit involved all political parties, unions and employer organisations and aimed to form a national consensus on economic policy. Hawke's links with business, built up during 22 years at the ACTU, were an effective foundation for such an approach, if an unusual one for a Labor Prime Minister.

-

'The Wages Accord' with unions, became a major part of government economic policy.

-

On 1 July 1983 the High Court upheld the government's right to block construction of the Gordon-below-Franklin dam, in Tasmania. The Government had used its powers under World Heritage legislation to prevent the Tasmanian government from building the dam.

-

The government floated the Australian dollar on international money markets and allowed the operation of foreign-owned banks as first steps towards deregulating the national economy.

-

Medicare health scheme was introduced on 1 February 1984.

Changes to Australia's education and training system began in 1984 and continued over the following years. Changes included amalgamations of smaller tertiary training institutions; creation of new universities from former Colleges of Advanced Education; the setting of national curriculum standards for schools; upgrading of the Technical and Further Education (TAFE) sector; and the establishment of national training and qualification standards.

Labor came to power in 1983 and inherited a deficit of $9000 million. This economic crisis informed much of the Hawke government's policy-making. The priority was to restore economic and employment growth by reducing high unemployment and inflation. Hawke, and his Treasurer Paul Keating, regarded good management of the ailing economy as vital. Both also believed the only solution lay in finding a structural and policy path that accommodated both labour and business.

This path was designed to increase the efficiency and competitiveness of Australian industry. Complementary industrial relations policies involved award restructuring and the introduction of enterprise bargaining. Despite the irony of a former trades union leader introducing these revolutionary changes, the Prices and Incomes Accord reduced industrial disputes, increased the social wage, and gave workers access to superannuation.

Financial assistance to low-income families was also increased. This achievement was overshadowed by Hawke's characteristically bouyant claim that 'By 1990 no Australian child will live in poverty'. The government also adopted policies integrating employment, education and training and acted to improve school retention rates.

The Whitlam government's Medibank scheme had been partially dismantled under the Fraser-Anthony Coalition government. Hawke established a new, universal system of health insurance under Medicare. The government also obtained agreement with the States on a single-gauge national rail system. The consensus rather than confrontation approach was also effective with voters. The Hawke government was re-elected in 1984, 1987 and 1990 in campaigns described as increasingly presidential. This record, for a Labor government, of four successive terms reflected Hawke's considerable and persisting popularity.

The greatest impact of the Hawke government flowed from the economic reforms that abandoned the traditional Labor reliance on tariffs to protect industry and jobs. During its term from 1983 to 1991, the government reduced the protection of Australian business and industry, increasing competition and at the same time achieving improved employment participation. Efficiencies in the tax system were also introduced.

In its first five years, from 1983 to 1987, the government decided on the moves to deregulate Australia's financial system. This involved 'floating' the Australian dollar (rather than tying its value to a gold standard or to another currency), and removing controls on foreign exchange. Direct controls on Australian interest rates were also removed, and foreign competition in banking was permitted. In its third term, from 1987 to 1989, the Hawke government abolished Australia's two-airline policy, removed export controls on bulk commodities and extended general tariff reductions.

Despite loss of popularity as measured by opinion polls, Hawke took the ALP to a record third term in office at the general election on 8 July 1987. The economic reforms of the 1980s owed much to close cooperation between Hawke and Treasurer Paul Keating. With the deterioration of the Australian economy by 1990, their working relationship also disintegrated and their rivalry intensified. With economic gains dissolving, support for the government dropped abruptly, as did Hawke's almost legendary popularity and authority.

In 1990-91 the Australian economy slid into recession and unemployment reached 11% in 1992 - the highest level since the Great Depression of the early 1930s.

Although Hawke had taken the ALP to a record fourth term in office at the general election in March 1990, uncertainty within the parliamentary party over his ability to win another election during a period of recession led to his removal as leader on 20 December 1991, when Keating made a second and successful challenge to Hawke's leadership. Hawke immediately resigned the Prime Ministership, which Keating then took over.

Just as Hawke had done with Bill Hayden ten years before, Keating provoked an open leadership contest in 1991. Keating claimed that Hawke had reneged on an agreement reached at Kirribilli House in 1988 about the transfer of the leadership. Hawke won a leadership ballot in mid-1991 and Keating retired to the back bench, giving up the Treasury portfolio.

On 12 December, a deputation of Hawke's ministers - Kim E Beazley, Michael Duffy, Nick Bolkus, Gareth Evans, Gerry Hand and Robert Ray - advised him to resign. He resisted, and a week later was persuaded to call another leadership vote. He was narrowly defeated by Keating, who became party leader and was sworn in as Prime Minister on 20 December 1991.

Hawke resigned from parliament soon after quitting as Prime Minister. He entered TV journalism, interviewing international political figures for the Channel 9 network. He subsequently pursued diverse business interests, and in 1994 published his political memoirs, The Hawke Memoirs.

- He was the Prime Minister but never a minister.

- He was the leader of the Opposition for only one month.

- The election win in 1983 (75 seats of the 125 in the House of Representatives and 30 of the 60 seats in the Senate) was the greatest Labor electoral win since John Curtin led the Labor victory in 1943.

- Hawke gained the highest popularity rating of any Prime Minister since the introduction of public opinion polls.

- He became the only Labor Prime Minister to have been removed by his own party while still in office.

- He was the longest serving Labor Prime Minister with four terms in office.

- He, like John Curtin, overcame an alcohol addiction and remained teetotal while in office as Prime Minister.

- Floated the Australian dollar and allowed foreign banks to operate in Australia.

- He became Prime Minister after only two years in parliament.

The reference material used to compile this page is listed below:

The design, layout and contents of this page are Copyright by Scaramouche© 2000 - 2005

All Rights Reserved.