Bought to you by Gavin A.K.A. "Scaramouche"

~ Privacy Policy ~ Copyright Statement ~ Site Map ~ Site Updates ~ Contact Me ~

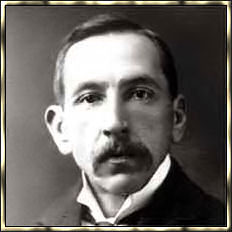

William (Billy) Hughes CH, PC, KC

11th Prime Minister.

National Labor Party

Nationalist Party

United Australia Party

Liberal Party

Bendigo

North Sydney

Bradfield

Victoria

Part-time law studies (1903)

Honorary Bachelor of Laws (Edinburgh, GIasgow, Wales and Birmingham).

Admitted to the Bar in 1903.

Farm worker, Saddler, Cook and a Deckhand on a coastal vessel.

Sydney Organiser of the Australian Workers' Union (early 1890s).

Barrister

Mary Campbell in the 26 June 1911, Christ Church South Yarra, Melbourne

Ethel (1889), William (1891), Lily (1893), Dolly (1895), Ernest (1897)

& Charles (1899)

With Mary Campbell:

Helen (1915)

PC (Privy Counsellor) 1916

CH (Companion of Honour) 1941

Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour

Grand Cordon Ordre de la Couronne de Belge

Privy Counsellor (Canada)

Fellow of the Zoological Society.

PLEASE NOTE: Both these links will open in a popup window

William Morris Hughes was born in London on 25 September 1862, the only child of Jane (Morris) and William Hughes. When his mother died, the 6-year-old child was sent to Llandudno, where he attended school. In 1874 he returned to London as a pupil-teacher at St Stephen's School, Westminster, and became an assistant teacher there in 1879. As a teenager, Hughes joined a volunteer battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. Hughes migrated to Queensland in 1884, aged 22. For the next two years he worked in the bush before arriving in Sydney as a galley-hand on a coastal steamer. He boarded in Moore Park, where he and his landlady's daughter, Elizabeth Cutts began a de facto marriage. Hughes did odd jobs, including umbrella-mending, and Elizabeth Cutts took in washing.

He moved to Sydney and later to Melbourne. Studying part-time, Hughes gained a law degree and became a barrister. Hughes was an early member of the colony's Australian Socialist League. After the failure of the maritime strike in 1890. The Hughes' shop stocked books and pamphlets and became a gathering place for young reformers, including William Holman. It was one of the centers for the debates and discussions that led to the formation of the Labour Electoral League in 1891 and the Socialist League in 1892. Hughes was a founding member of both leagues as were two other future Prime Ministers, Joseph Cook and Chris Watson.

Hughes was convivial and persuasive, his 'gift of the gab', lively mind and fund of rollicking stories ensured he was known in a widening circle. He preferred to be known as 'Will' and disliked being called "Billy"'. His intelligence was sharp, he read widely in English literature and history, and a had a caustic turn of phrase. During this period, Hughes became enthusiastic about the ideas of Henry George, whose social reform theories centered on a single tax on the unimproved rental value of all land. Street-corner speakers expounded George's ideas, and Hughes was the Balmain Single-Tax League's star performer.

Though an advocate of democracy, he opposed womanhood suffrage, arguing that women were more conservative than men. In 1894 Hughes worked in outback New South Wales as an organiser for the Amalgamated Shearer's Union. Elizabeth Cutts managed the Balmain shop and raised their two infant daughters. Their son had died in 1892, a year after his birth.

Hughes was a candidate in the New South Wales election at the end of 1894, and narrowly won the waterfront seat of Lang for the emerging Labor Party. He retained it until Federation in 1901. In 1899 he organised Sydney's wharf labourers and remained their union secretary for the next 17 years. He founded the Waterside Workers Federation and was elected its president, and at the same time was involved in the Trolley, Draymen and Carters Union and was its president. A moderate unionist, he preferred negotiation to industrial action.

A believer in free trade, he was instrumental in the downfall of Free Trade Premier George Reid in 1899. Like Reid, Hughes was sceptical about the proposed Australian Constitution and thought it too conservative. Hughes was thus an opponent of Federation and of its leading advocate, New South Wales parliamentarian Edmund Barton. Hughes nevertheless stood for the first federal election in March 1901 and won the seat of West Sydney, which included his former Lang electorate. As early as the first parliament, he urged compulsory military service for national defence and argued for an Australian naval force.

From 1901, Hughes lived mostly in Melbourne, where parliament sat and where the new Commonwealth government departments were established. His family remained in Sydney, where Elizabeth Cutts ran the bookstore and cared for their five children, aged from 2 to 10 years. Hughes had studied law part-time for years, and was admitted to the bar in 1903. The family then moved to Gore Hill, across the unbridged Sydney Harbour from their Balmain neighbourhood. When the first federal Labor ministry was formed in April 1904 under JC Watson, Hughes became Minister for External Affairs. Though the Watson government lasted only four months, this was an important experience of Cabinet office.

Elizabeth Cutts died from the heart disease she had suffered for some years on 1 September 1906. Hughes remained in Melbourne and his 17-year-old daughter Ethel raised the children in Sydney. The following year, as an Australian delegate to a shipping conference, Hughes made his first trip back to England since he had emigrated 23 years before.

In October 1907, the Labor Caucus elected Hughes deputy leader when JC Watson resigned the leadership of the federal parliamentary party. When the Deakin government fell in November 1908 and Andrew Fisher was sworn in as Prime Minister, Hughes became his Attorney-General. Hughes was a lively and engaging writer. From 1907 to 1911, he wrote a weekly column for the Sydney Daily Telegraph, under the heading 'The Case for Labor'. In 1909 Hughes' law career reached an important threshold when he 'took silk' and became a King's Counsel.

Hughes became Attorney-General for a second time after Labor's landslide victory at the election on 13 April 1910. During its three years in office, the Fisher government tried to widen the federal government's powers through two referendums. When the April 1911 referendum failed, Hughes sought to illustrate the problem by taking on the Coal Vend, a cartel of coalmine owners and shippers. Though Hughes lost the case, he gained enough ground to justify a second referendum. Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia approved the extension of Commonwealth power, but the proposal was lost overall.

In June 1911, he had married Mary Campbell and set up home in Melbourne.

In the 1913 federal election Labor lost office to the 'Deakinite' Liberal Party, led by Joseph Cook after Alfred Deakin's retirement that year. Twelve months later the Prime Minister called for, and was granted, the first double dissolution of the Commonwealth parliament.

With the outbreak of World War I on 4 August 1914, Hughes argued that Labor should postpone the election by offering a political truce to Prime Minister Joseph Cook, but Caucus was not convinced. Then, at the election on 5 September 1914, a Labor government was returned. Andrew Fisher became Prime Minister for the third time, and Hughes was again deputy Prime Minister and Attorney-General. Hughes had charge of the legislation that put the country on a war footing, and he drafted and enforced the regulations under the War Precautions Act. From the beginning he was a central figure of the government's wartime administration.

Hughes spent much time re-organising the metals, wheat and sugar industries. Before the war, German companies had controlled the market in lead, copper and zinc. All were crucial in munitions manufacture. Hughes was determined to end this monopoly and, with the active support of businessman William Robinson, largely succeeded. In the case of wheat, 'by the end of 1915 the Commonwealth had, in effect, made itself responsible for the entire handling and shipping' of the crop. A similar arrangement was worked out for sugar. Australia was at war when WM Hughes became Prime Minister, replacing Andrew Fisher, in October 1915. Hughes favoured conscription for overseas service as a means of maintaining Australia's supply of troops to the war zone. This stance led to his expulsion from the Labor Party in late 1916. Commissioned to form a new ministry, he carried on for three months as head of the National Labor Party (with support of the Liberal opposition). His 'splinter' Labor Party combined with the Liberals in 1917 to form the Nationalist Party, which was confirmed in office by the general election held later that year.

Andrew Fisher increasingly delegated authority to his eager, active deputy leader. For two months in mid-1915 Hughes acted as Prime Minister while Fisher was in New Zealand. Fisher's energies were flagging and in October 1915, with some pressure from his colleagues, he retired to succeed George Reid as Australia's High Commissioner in London. On 26 October 1915, Hughes was unanimously chosen by Caucus as the new Labor leader, and the following day became Prime Minister. Hughes visited England on 7 March, and spent the next three months in Britain and visiting Australian troops in the front line in France. Despite frequent ill health, Hughes made rousing speeches that were received enthusiastically. In an audacious coup, Hughes circumvented British wartime controls on shipping by secretly purchasing fifteen cargo vessels on behalf of the Australian government. These ships were to convey Australia's wheat and other commodities to British markets, and became the foundation of the Commonwealth Shipping Line.

One of the reasons for Hughes' London visit had been to improve communication with the Britain's Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith on Australia's concern about Japan's activities in the Pacific. Despite Hughes' opposition, Britain acceded to Japan's occupation of former German territories. A popular wartime leader who was affectionately tagged 'the Little Digger', Hughes visited Australian troops on the western front and, after the war, represented Australia at the Versailles Peace Conference.

He arrived in Australia on 31 July 1916 to find the country divided on the question of compulsory military service overseas. The conservative parties, the press and even most church-leaders had by then come out in support of conscription. Trade unions however condemned the suggestion, and Labor activists like John Curtin and James Scullin in Victoria were organised in their opposition. Hughes, because he had seen Australian troops in the hospitals and camps of England and in the trenches in France, believed passionately that urgent reinforcements were necessary. He called a referendum to obtain support for his proposal to introduce conscription. After a bitter and divisive campaign, his proposal was defeated on 28 October 1916.

Hughes and other Labor members, like JC Watson, who had advocated conscription were then expelled from the Labor Party. He also lost the position as union secretary for the Sydney wharf labourers a position he had held for 17 years.

At a meeting in the party room in Parliament House in Melbourne on 14 November, Hughes led his followers out of the Labor Caucus. They then formed a "National Labor Party" with sufficient numbers in the House of Representatives to retain government under Hughes. A new ministry consisting entirely of members of the breakaway group was sworn in the same day. After lengthy negotiations, on 17 February 1917 a new Nationalist government was formed. Hughes attempted to force a resolution through the Senate requesting the British parliament to amend Australia's Constitution so as to extend the life of the parliament. The ploy failed and the scheduled election went ahead. Despite the referendum defeat only 6 months previously, Hughes easily won the general election on 5 May 1917. During the election campaign, when questioned about conscription he had pledged that if 'national safety demands it, the question will again be referred to the people'.

The most difficult year of the war was 1917. Industrial unrest resulted in the most serious strike in New South Wales since the 1890s, and it was put down with severity by the State government. By November the worsening situation of the Australian Imperial Force in France and a sustained drop in recruitment persuaded the government that conscription was essential to providing reinforcements. In view of his promise during the election campaign, Hughes was compelled to call another referendum. After an even more bitter campaign than the year before the referendum was held on 11 December 1917. Again, the government's proposals were defeated.

Hughes had a major influence on Australia's external relations in the first half of the 20th century. His conduct of matters while in Paris attending the Peace Conference from January to June 1919 with Navy Minister Joseph Cook was the peak of this achievement. His arguments pushed the case for Australia and the other British dominions to have independent membership of the League of Nations, despite the reluctance of the United States. A leading figure in the Reparations Commission, Hughes argued that Germany must pay for the costs of the war and pressed for Australia to be compensated for its war-related expenditure.

On the issue of former German New Guinea, Hughes fought for Australia to gain control of the territory, in the face of President Wilson's strong opposition. Wilson reminded Hughes that he spoke for only five million Australians. To this hughes replied that he also represented sixty thousand dead. This was a pointed reminder that even though Australia's population numbered less than a twentieth of that of the USA, its tally of war dead was more than half the USA's. He succeeded in securing Australian control of Germany's colonial possessions in New Guinea and the adjacent archipelagos. A special class of mandate was created, allowing the territory to be administered as an integral portion of the mandating country. The third point Hughes pursued in Paris was to block the attempt of the Japanese delegation to insert in the covenant of the League of Nations a clause guaranteeing 'equality of nations and equal treatment of their nationals'. Seeing this as a threat to the White Australia policy, Hughes successfully lobbied the commission and the vote was lost.

On 28 June 1919, Hughes and Cook lined up with the representatives of the nations in the palace's Hall of Mirrors and signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Australia. At the end of the conference, Australia was a full member of the League of Nations and the former British Dominions had achieved a new international status. Returning a hero to Australia, Hughes won the election comfortably in December 1919. After returning from Versailles, Hughes progressively lost control over his government. The newly emerged Country Party, which soon became influential, refused to support any government which he led. The Nationalists lost their majority at the general election in December 1919, and had to rely on support of the newly emerged Country Party (CP), which proved antagonistic to Hughes. The Nationalists were increasingly torn by internal dissent, much of it arising from dissatisfaction with Hughes' leadership.

At a general election on 16 December 1922, in which five Victorian and South Australian Nationalists fought on the 'Hughes Must Go' platform, the party lost further ground. During the next two months, as the Nationalists and the CP sought some agreement with each other, the CP made it clear that any coalition arrangement would depend on Hughes' departure as Nationalist leader. The 1922 general election was won by the Nationalist Party, with the support of the recently formed Country Party. When Country Party members refused to accept Hughes as leader, he resigned. In 1923 he was replaced as Prime Minister by Stanley Melbourne Bruce. The S.M. Bruce - E.C.G. Page Nationalist-CP coalition government took office on 9 February 1923.

In 1929 Hughes precipitated the fall of the Bruce-Page coalition government by voting with Labor against the government on a censure motion. Bruce then expelled Hughes from the parliamentary Nationalist Party on 22 August 1929. On 10 September, Hughes moved the deferral of an arbitration bill and this, because of it's support, effectively bought down the government. In October 1930, Hughes launched a new party - the Australia Party - which soon withered away after polling poorly in New South Wales state elections later that month.

In March-May 1931 a new non-Labor party, the United Australia Party, had been formed with J.A. Lyons' as it's leader. Hughes joined them after his expulsion from the parliamentary Nationalist Party. The newly formed UAP defeated J.H. Scullin's Labor government at a general election on 19 December 1931 and assumed office on 6 January 1932. In April 1939 J.A. Lyons died; E.C.G. Page became caretaker Prime Minister. When a leadership crisis afflicted the UAP and the CP quit the coalition.

When J.J.A. Curtin's Labor government took office in October 1941, Hughes worked cooperatively with Curtin as a member of the Advisory War Council and opted to remain membership of the council after the UAP withdrew from it in 1944. For this he was expelled from the UAP. He joined the newly formed Liberal Party in 1944, and remained a back bencher after Menzies led the party to victory at the December 1949 general election. Hughes remained in parliament and was a senior member of non-Labor governments until his death in 1952.

At his death in October 1952, Hughes had spent over 58 continuous years as a member of parliament, almost 51 of these in federal parliament. He was the last politically active member out of all those who had entered parliament in 1901. His period of membership remains a record in Australia. He has been the only one among 24 Prime Ministers to have been Prime Minister on both sides of politics - Labor and non-Labor.

Hughes' state funeral in Sydney was one of the largest Australia has seen: some 450,000 spectators lined the streets to watch the passage of a flag-draped coffin on a gun carriage accompanied by a 3-km long procession of mourners.

- In 1915 founded Advisory Council for Science and Industry, later CSIRO.

- No parliamentarian has surpassed his 51 years and 7 months of continuous service as a member of Australia's House of Representatives - from the 1st parliament in 1901 to the 20th in 1952

- Hughes was a founding member of the Labor Party in New South Wales.

- He became a founding member of the Nationalist Party in 1917

- He was a founding member the United Australia Party in 1931

- He was a founding member the Liberal Party in 1945

- Helped found three political parties, and was expelled from them all:

the Labor Party (in 1916),

the Nationalist Party (in 1929),

the United Australia Party (in 1944)

- He had more than 100 prime ministerial secretaries.

- The longest-serving Prime Minister until 1956 when Robert Menzies overtook his record 7 years 3 months and 14 days in 1957

- Completed fifty years of continuous parliamentary service in July 1944.

- Honoured with fifteen 'Freedom of the City' awards - more than any other Prime Minister.

The reference material used to compile this page is listed below:

The design, layout and contents of this page are Copyright by Scaramouche© 2000 - 2005

All Rights Reserved.