Bought to you by Gavin A.K.A. "Scaramouche"

~ Privacy Policy ~ Copyright Statement ~ Site Map ~ Site Updates ~ Contact Me ~

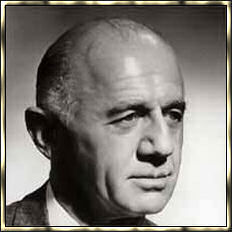

Sir William McMahon KCMG, CH, PC

25th Prime Minister.

Sydney Grammar School (1923-26).

University of Sydney.

Bachelor of Economics 1949 (Sydney).

CH (Companion of Honour) 1972

KCMG (Knight Commander of The Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael St. George) 1977

Appointed Lieutenant, 1st Infantry Battalion.

Discharged 1945 with rank of Major.

PLEASE NOTE: Both these links will open in a popup window

William McMahon was born on 23 February 1908, one of the four children of solicitor William McMahon and Mary Anne (Walder) McMahon. His mother died when he was 9 years old, and his father when he was 18. McMahon was raised by his aunt and uncle, Elsie and Samuel Walder, a Sydney businessman. McMahon went to Sydney Grammar School from 1923 to 1926, then to the University of Sydney. He graduated in 1933 with a law degree and became a solicitor with leading Sydney legal firm Allen, Allen & Hemsley. After war was declared in 1939, McMahon joined the 2nd Australian Imperial Force.

A hearing problem - later corrected - kept him from active service. He spent the Second World War on essential, but unglamorous, home service duties and was discharged with the rank of major. After being discharged from the AIF he enrolled at the University of Sydney to study economics and graduated in 1949 with distinction. McMahon won Liberal Party pre-selection for the seat of Lowe at the 1949 federal election. He won and took his seat in the 19th parliament on 22 February 1950. In March he spoke on the Commonwealth Bank Bill, introduced by Treasurer Arthur Fadden to repeal the Chifley government's 1947 Act. In April, he spoke on the Communist Party Dissolution Bill, introduced by Prime Minister Robert Menzies in an attempt to outlaw Communism in Australia.

The Senate, where Labor had a majority, refused to pass the Commonwealth Bank Bill in 1951 and Robert Menzies obtained a double dissolution of parliament. This was the first double dissolution since 1914. The coalition was returned, with increased numbers in the Senate. Entry into the Commonwealth Parliament, at the age of 41, enabled McMahon to demonstrate talents for hard work and Organisation. Menzies made him Minister for the Navy and Air in 1951 and, from 1954-71, he progressed steadily and solidly through the portfolios of Social Services, Primary Industry, Labour and National Service, the Treasury and Foreign Affairs. He made such a success of Primary Industry that Arthur Fadden demanded the return of the portfolio to the Country Party.

As a minister, McMahon proved himself a supreme "organisation man" who worked hard and well even if he lacked the flair of some other politicians. His diversity of portfolios gave him immense administrative experience, which sometimes irritated other ministers because it caused him to pontificate on matters which were not his responsibility. He dealt firmly with trade union leaders, although he was said to show less humanity than Harold Holt. Altogether he earned respect as a pillar of the Liberal Party and, when Holt succeeded Menzies, he stepped into Holt's place as deputy leader.

The coalition lost ground at the 1954 election, but when Prime Minister Robert Menzies obtained another early dissolution of parliament in December 1955, the Menzies-Fadden coalition was returned with an increased majority. Among the changes in the new ministry sworn in on 11 January 1956, was a division for the first time into 18 Cabinet and nine 'outer ministry' portfolios. The portfolio responsibilities of Minister for Commerce and Agriculture John McEwen were divided into two Cabinet posts. Separate departments of Trade and of Primary Industry were created, with McEwen Minister for Trade and William McMahon Minister for Primary Industry. The choice of McMahon for this traditional Country Party area of responsibility was thought curious, and even comical. Born and educated in exclusive Sydney circles, McMahon had neither interest in nor knowledge of rural issues. Press gallery journalists noted that the split portfolio created a problem for the junior coalition partner as the Country Party already had their Cabinet quota, the senior posts of Treasury and Trade. Unwilling to exchange either of these, the compromise solution was to choose an inexperienced Liberal junior minister who would be guided by his predecessor, John McEwen.

In fact McMahon's two years in Primary Industry sowed the seeds of a bitter lifelong enmity between the novice and his intended mentor. Promoted to this more senior post, McMahon took his new responsibilities seriously. Far from seeking the advice of his experienced coalition colleagues, he looked to the senior officials of his department, who had long experience in the former Agriculture Department. With their help and his own intelligence and determination, McMahon learned about every aspect of his new responsibilities. He was soon able to deal effectively with Question Time, and proved to be a capable administrator and a shrewd negotiator with pressure groups large and small. It was not long before he clashed with his predecessor, John McEwen, over a butter price stabilisation scheme, and then began to move for a long-neglected reconstruction of the dairy industry. For the Country Party, drawing much of their electoral strength from dairy-farming districts, this was an unforeseen and unwelcome intrusion. For McEwen, a dairy farmer when McMahon was still at primary school and responsible for the portfolio for the previous seven years, it was an unforgivable affront.

In the new Menzies-McEwen ministry McMahon was promoted to the portfolio of Labour and National Service. In his new portfolio, McMahon proved himself as able as before, mastering the issues and as tough at negotiating with the waterfront unions as he had been with the primary industry pressure groups. In June 1964 McMahon was appointed to the additional Cabinet post of Vice-President of the Executive Council. As Minister for Labour and National Service, McMahon was responsible for the government's compulsory military service legislation. Introduced to parliament on 11 November 1964, the Bill provided for compulsory registration of all 20-year-old men, with a ballot to select at random those who would be called up for military training, and service overseas if necessary. The immediate concern was the Malaysian crisis. By the time the law was enacted, the government had announced that a battalion of Australian infantry would be sent to South Vietnam to assist United States forces in the war against the North Vietnamese Communist government.

In December 1965 William McMahon and Sonia Hopkins married in Sydney. At the age of 57 McMahon had seemed a confirmed bachelor.

After Robert Menzies retired from parliament in January 1966, Harold Holt was elected as party leader and William McMahon as deputy. Holt was sworn in as Prime Minister and McMahon as Treasurer on 26 January 1966. McMahon's ministerial record and abilities qualified him for the leading Cabinet post, but it also placed him on a collision course with Minister for Trade and Industry and deputy Prime Minister John McEwen. Their conflict had continued for the decade since McMahon had shunned McEwen's advice on the primary industry portfolio. Over time their differences had intensified and widened, attracting opposing champions in the press. McMahon received better press from legendary press gallery journalist Alan Reid in Sydney's Daily Telegraph, owned by Frank Packer. McEwen seemed to be more often supported by the Fairfax-owned Sydney Morning Herald and Canberra Times. McEwen complained bitterly of McMahon's relationship with business journalist Maxwell Newton. Both suffered from Canberra's 'inner circle' press - the newsletters and columns of journalists such as Frank Browne and Don Whitington. The regular flow of Cabinet leaks filling these willing hands not only caused questions in Cabinet, but had Governor-General Lord Casey discussing the problem with Director-General of Security, Charles Spry.

One of the major confrontations was over foreign investment, with McMahon and the Treasury in favour of using overseas capital for development. McEwen was firmly against this, and attempted several times to secure Cabinet agreement to the establishment of an Australian Industry Development Corporation as a lending body. Other contentious issues were Britain's second and successful application to join the European Economic Community in 1967, and Australia's response to Britain's devaluation of the pound sterling. In November 1967, while McEwen was overseas, Cabinet accepted McMahon's recommendation not to follow Britain and devalue the dollar. On McEwen's return, he made public his strong disagreement. Prime Minister Harold Holt secured McEwen's agreement not to force the issue, but McMahon moved on other areas of direct conflict with McEwen. Holt and other Cabinet members had discussed all these issues with McMahon, including his connection with journalists who wrote articles criticising McEwen and policies within the Trade and Industry portfolio.

Then, in an unusual move, on 8 December 1967 Governor-General Lord Casey met with McMahon and attempted to act as mediator. McMahon questioned the constitutional propriety of Casey's intervention, but the two men had a lengthy meeting. McMahon made a written record of the meeting, and for the next week continued to try to gather support against McEwen. He phoned Holt at his Portsea holiday house on Sunday, 10 December to question him, met with other ministers and, on 15 December, met Holt at Parliament House to insist Holt have a copy of all his notes on the matter.

That weekend, Holt disappeared while swimming near Portsea, Victoria on Sunday, 17 December, and two days later was presumed dead. As deputy Prime Minister McMahon planned a party meeting the following day, 20 December, for a leadership ballot. This move was pre-empted by McEwen's statement to the Governor-General, to McMahon himself, and to the press, that he would not serve in a McMahon government. McMahon's own colleagues moved promptly to avoid a crisis in which the coalition government would fall, and Paul Hasluck, Allen Fairhall, John Gorton and Party Whip Dudley Erwin all saw the Governor-General on Monday, 18 December after McEwen, and before McMahon. Lord Casey commissioned McEwen as Prime Minister the next day, 19 December 1967.

McMahon did not stand for the Liberal leadership ballot on 9 January 1968, and the party chose John Gorton over Paul Hasluck, Billy Snedden and Leslie Bury. McMahon was again elected deputy leader and remained Treasurer in the Gorton-McEwen coalition government. In the new Gorton-McEwen ministry McMahon succeeded Hasluck as Minister for External Affairs, renamed Foreign Affairs on 6 November 1970. The third Gorton ministry was sworn in on 12 November 1969. The coalition had fared badly in the election and McMahon unsuccessfully challenged Gorton for the leadership.

In 1970, before his retirement from parliament on 1 February 1971, McEwen secured the establishment of the Australian Industry Development Corporation. On 8 March Malcolm Fraser resigned his Defence portfolio, precipitating John Gorton's resignation. On 10 March McMahon won a ballot for leadership of the parliamentary Liberal Party, but Gorton was elected as deputy leader.

The dogged persistence which had taken McMahon to the highest office in the land saw him continue as a member of Federal Parliament until 1982. He was an outspoken critic of economic policy - both Liberal and Labor. Knighted in 1977, Sir William's final years were blighted by cancer to which he succumbed in March 1988.

- 63 years old when he became Prime Minister, the oldest next to John McEwen, 67.

- He was the first to hold the House of Representatives seat of Lowe, created in the 1949 electoral distribution.

- When his government lost office at the 1972 Federal elections, he became the first Prime Minister to lose office at the ballot box since Ben Chifley lost the 1949 election.

- The McMahon ministry was the first to have a Minister for Aboriginal Affairs.

- He announced the withdrawal of Australian troops from Vietnam.

- His Liberal-Country Party coalition government was in power non-stop for 23 years.

- His Government was responsible for the establishment of the first Aboriginal Legal Service, in Redfern, Sydney, in 1972.

The reference material used to compile this page is listed below:

The design, layout and contents of this page are Copyright by Scaramouche© 2000 - 2005

All Rights Reserved.